Artist Lorna Simpson moves between the micro- and the macro- but her work is always cosmic. Her current exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles is titled Everrrything and can rightly be said to encompass a whole universe — several universes actually. As a practical matter, there are sculptures, mixed media paintings, collage suites and moving pictures; materially there are found objects, as well as vernacular and original objects and images, recombined and produced with wood, stone, glass, fiberglass, ink, gesso, screenprinting, pastel, handmade paper, magazine pages, video and activated sound.

Narratively, Simpson tracks operations of mythology, metaphor and memory across small, precious found things, reimagined popular culture icons, gestural portraiture and atmospheric abstract landscapes. Conceptually, she’s confronting problematic tropes of art history, cultural power structures and environmental degradation. Knowingly, she’s referring to the sheer weight and scope of recent and historical geopolitical health and social traumas — and all the work that remains undone. Coincidentally, a new revised monographic survey encompassing Simpson’s work of the last three decades has just been released, following an extensive period of engagement with her own archive, reconsidering her relationship with art history. So yeah, Everrrything really means everything.

Lorna Simpson: Stacked Stones/Vibrating Cycles, 2021. Bluestone, wood, paint, black obsidian singing bowls, mallets, 15 stacks. Installation view, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, 2021 (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

The exhibition is heralded by an enigmatic outdoor sculptural installation in the gallery’s courtyard; you must pass it to reach the doors to her show. Stacked Stones/Vibrating Cycles is 15 piles of slate-like bluestone, stabilized with painted wood plinths and topped with black obsidian singing bowls for which playing mallets are available at the desk. Both casual and intentional, the stones invite questions. “The stones are from the Northeast corridor,” Simpson tells L.A. Weekly, “like New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut. I wanted to literally bring something that is part of the American landscape to a different part of the landscape.”

They hover in a liminal space between construction and destruction; they are not finished until someone plays the bowls. And they were cleaved by hand, which is part of their beauty but also part of their meaning, as they invite us to ponder questions such as typically gathers and breaks and sorts and stacks and uses these kinds of materials and for what purpose. Are they a barrier or a shelter, a boundary or a placeholder; salvaged from ruins or awaiting their functional destiny? Are they accidents or totems, coded pathfinders, altars? Are they permanent? There’s a mysterious Andy Goldsworthy spirit at play, plus a tousled and energized Carl Andre echo, along with a conceptual and economics-inflected story that channels Courbet’s Stone Breakers in its divergent perspective on the value of labor and the landscape.

Installation view, Lorna Simpson. Everrrything, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, 2021. (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

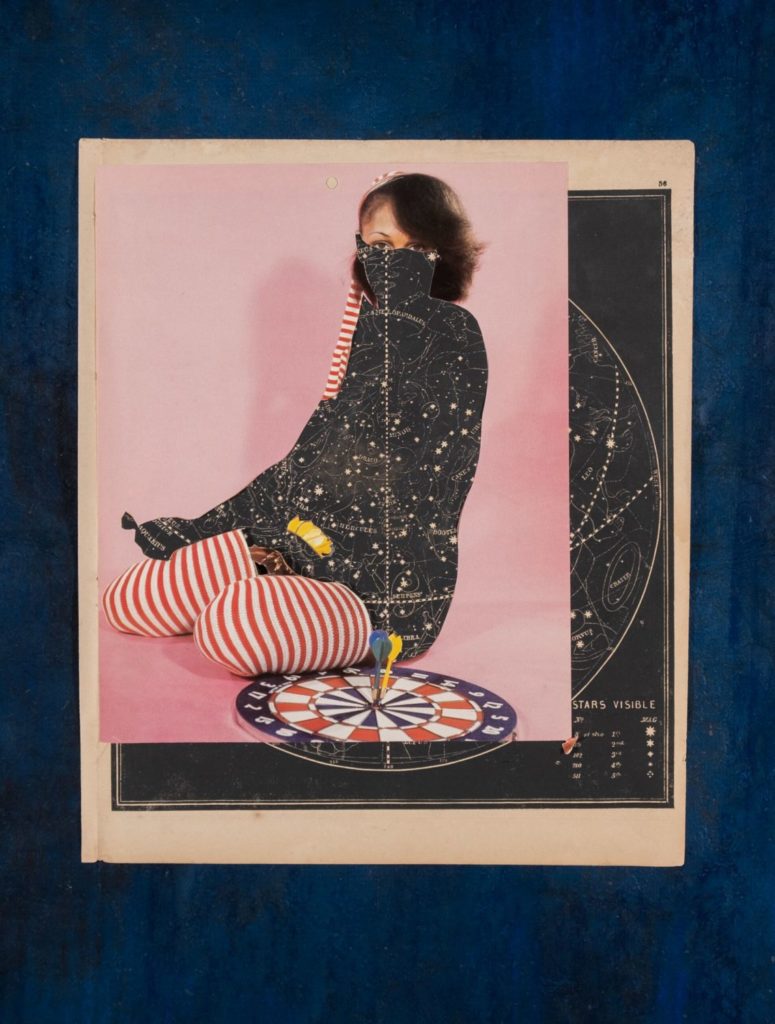

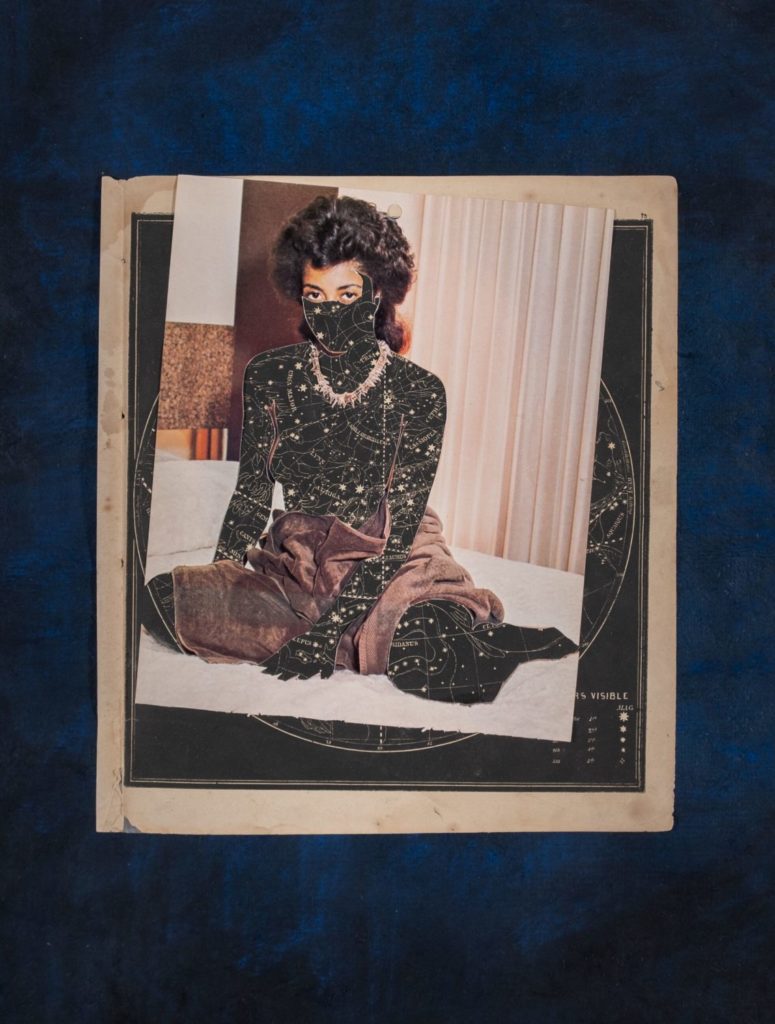

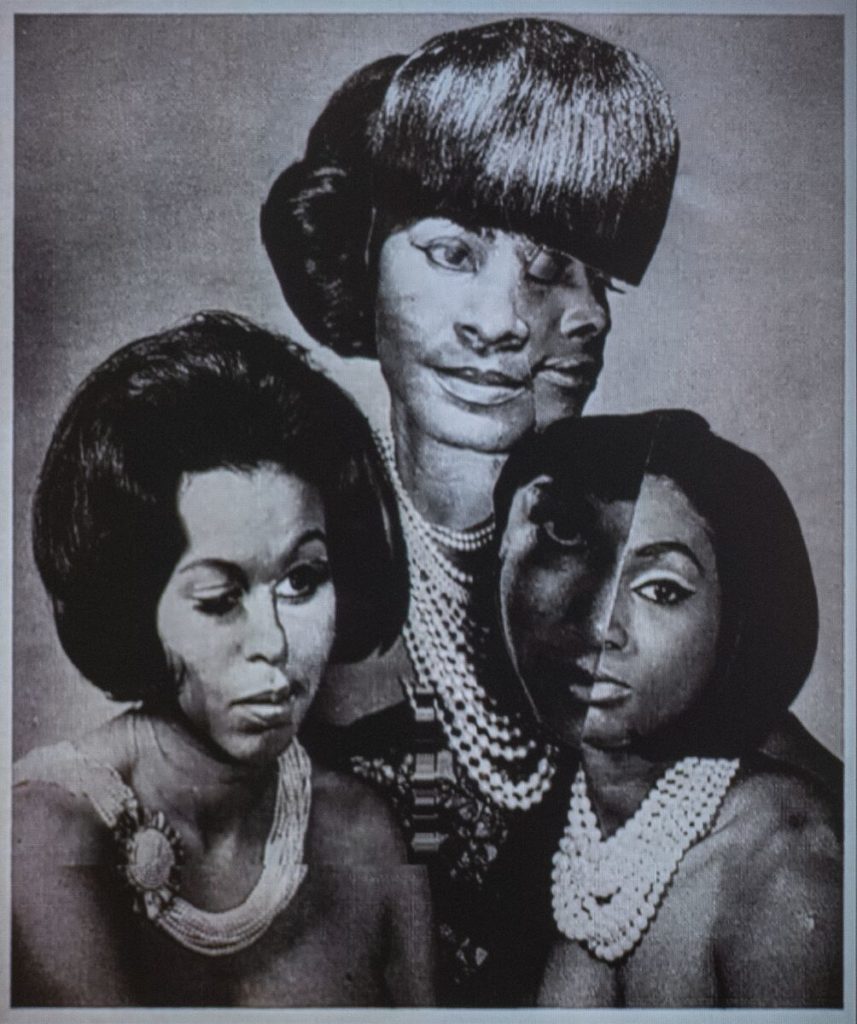

Once inside, a center line of dozens of collages wraps around the vast perimeter, organized in thematic subsets but all continuing the artist’s ongoing exploration of the collage medium through her recontextualizing of advertising photographs (which are both portraits and socio-cultural fictions) from vintage issues of Ebony and Jet magazines. Into her elegant reconfigurations, Simpson further incorporates found photo booth snaps (which prefigure selfies as they demonstrate both a slight agency on the part of the subject and their staged performative construction of their own image). With motifs culled from photojournalism of the natural world, 19th century celestial maps and scientific textbooks — set amid luxurious backings of indigo-dyed paper and an incandescent blood orange — works such as the Everrrything and Observing the Universe series describe a full society of women in a way that reveals female, and especially Black female, existence as an endless navigation of fiction, projection and aspiration.

Lorna Simpson: Observing the Universe, 2021. Collage and pastel on handmade paper, 5 parts, Each: 24 x 17 in. (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

Lorna Simpson: Observing the Universe (Detail), 2021. Collage & pastel on handmade paper, 5 parts, Each: 24 x 17 in. (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

“Working the collage is a kind of analog way of playing with the imagination,” Simpson says. The video Walk with me is a simple but effective and affecting film loop that essentially feels like actual footage of her brain when she’s got the scissors out and is ready to play. In the collages she often splices faces, so that what seems like one visage is actually constructed of two. The optical and metaphoric appeal of this surreal nuance is both hypnotic and unsettling.

There’s a hefty sculpture, Hypothetical Physical States, installed inside the galleries containing large landscape paintings. It’s a callback to the stacking sculptures outside, with the same blue painted wood blocks that are used for stabilizing the cairns. But it has since become apparent that this is also the same blue that lights up the painted portraits and dominates the landscape paintings. But rather than participatory bowls, this supports a domed glass bell jar, stilling and containing the energy and the mystery rather than amplifying it.

Lorna Simpson: Reoccurring, 2021. Ink and screenprint on gessoed fiberglass, 102 x 144 x 1 3/8 in (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: James Wang)

As the sculptures interrupt your movement through the spaces and engage your body and other senses in the narrative dimensions of the work — and as the collages draw you into closer intimacy with the work through the seduction of their tiny details and pinpoints of light — the large-scale mixed media paintings appear with an operatic sweep, creating moods and atmospheres that you can enter right into, be enveloped by and experience almost from within. Large (about 5 by 8 feet) silkscreen on gessoed fiberglass, their pigmented surface topography contains a wealth of flickering detail. You can see the many layers of process technology, the way the silkscreening has of pulling apart like newsprint, the artist’s hand evident in gravitational drips and surface interventions. The landscapes, like the constellation maps in the collages, are from the 19th century; and her appropriation of them speaks to how American mythologizing of the landscape is just as insidious, misogynistic and anti-Black as our commercial culture and art history have been.

Lorna Simpson: Everrrything (Detail), 2021. Collage and pastel on handmade paper, 10 parts, Each: 24 x 17 in. (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

Many of these monumental mixed media works had been started in early 2020 or even late 2019 in her New York City studio — a place she was more or less unable to access for an unexpectedly long time, having moved into a second home here in Los Angeles just as the pandemic lock-downs set in. “Going back to New York in September of 2020,” Simpson says, “I had a bunch of work that was in process. Walking back in the studio and with everything that had happened, I changed my relationship to the work, to its interests and even to the kind of day-to-day pace of making it. I really recognized that my entry back into the work was going to be different, and was going to require that I play with the work in a different way in order to move forward.”

Not only because of supply chains, staffing structures and safety concerns but also because of folks’ states of mind, there was what Simpson calls a need for patience, ironically coupled with time pressures that made it impossible to overthink anything. “There was not enough time for that! I just had to go with my gut and ride with my instincts and intuition,” she says. “And I think it’s kind of a gift in a way, because I was like, oh, this is interesting. I can go at things a little differently, with regard to quality of life… and also be affected by what had happened in the interim.”

Lorna Simpson: Walk with me, 2020. Single-channel video installation, color, silent, looped. Duration: 14 seconds (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

While Simpson is adamant that this is not work about Covid, the idea that there was enough time for the pieces to begin reflecting the experience — an experience that is still unfolding to this day — is palpable. The large portrait Observer is an ethereal yet statuesque figure whose blue robes are bathed in an aura of light that bursts from within an enveloping shadow, giving the work an already-ancient, ancestral quality. Landscapes like the majestic, institutional scale Reoccuring have a foundation of this same emotional and temporal hybridity, both dissolute and still gathering transformative energy. Its expanse of the now-familiar deep blue is the most cinematic; its rocky shoreline cliffs evoking travel and migration with a prologue of colonialism and kidnapping; at the same time, the woman’s face emerging from within the rock possesses its own powerful ancestral energy, reaching into both the past and the future at the same time.

Lorna Simpson: Time, 2021. Ink and screenprint on gessoed fiberglass, 102 x 144 x 1 3/8 in. (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

Storm is a bifurcated vertical scene in which the horizon line divides abstract versions of a gray rainy sky above a radiant blue water and in its center is a partly submerged, swimming and floating woman, seeming to emerge from the gyre. Pieces of architectural geometry pin the scene’s movements in place and keep the viewer at a bit of distance. In Time, this format is reversed — the ground is streaked, the sky luminous, the woman more poised but suspended upside down like a tarot card. She is contained in a square of lapis (the same blue from the portraits, the collage settings and the painted wood braces among the stones), her regal profile almost like what you’d expect to see on money. These works ask questions, Simpson says, about how much control we really have over our lives, our fates and our sanity.

Lorna Simpson : Above Head, 2021. Bronze, vintage woodblock print clippings, handmade paper, liquid acrylic, pastel, photo booth portraits, 218 parts, Unique Installation. Overall dimensions: 93 1/2 x 194 1/2 x 1 in. (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

“Those things are present in my mind, you know, one’s belief system and in a way what you’ve known and experienced — it’s important to keep that as a constant conversation,” Simpson says. “Even if the other person isn’t, say, prepared or wanting to engage with that, there is a kind of centering that is important to maintain. I’ve always been a critic and also skeptical of art history, in terms of its canon, in terms of what it privileges.” she says. “I think I’ve always been aware of that. And even in my own career, I have had to maintain my own language for the way I speak about the work. I call it the Toni Morrison thing. Like, you’re asked a question, and you can engage the question, but it doesn’t mean you need to answer it. You need to reframe the question, so that your answer makes sense.”

Everrrything is on view at Hauser and Wirth in the downtown arts district through January 9; hauserwirth.com.

Installation view, Lorna Simpson. Everrrything, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, 2021. (© Lorna Simpson | Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth | Photo: Jeff McLane)

The post Lorna Simpson: <I>Everrrything</i> is Illuminated appeared first on LA Weekly.

0 Commentaires